A MIDDLE CLASS: THE ‘ÉVOLUÉS’

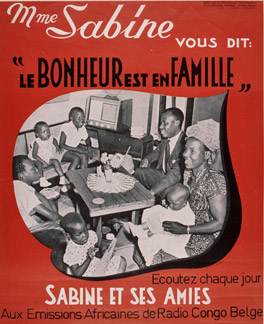

Madame Sabine vous dit: Madame Sabine vous dit:'Le bonheur est en famille' Coll. RMCA |

The word 'évolué' is a poorly defined term that applies to Congolese deemed 'civilized'. Some say that on the eve of independence only 1% of the population claims to be 'évolué'. Indeed, the colonial administration impedes the development of a middle class – 'no elite, no problems'. It prefers to educate as many children as possible at the primary school level. After the Second World War, the administration creates the civic merit card. Born colonial subjects, Congolese are excluded from enjoying the same rights as Belgian citizens. The education of girls is neglected, relative to the education of boys. THE CONGOLESE PRESSWell before the 1950s, Christian missions, major private companies like the Union Minière du Haut Katanga and institutions such as the Force Publique create magazines and newspapers for the Congolese, headed by Europeans – the first Congolese journalists don't appear on editorial staffs until after the war. In 1934 and 1935, 'évolués' can express themselves in the first non-confessional journal, Ngonga, which meets with opposition from the colonial administration. Beginning in 1954, ABAKO publishes the periodicals Kongo dia Ngunga and Congo pratique; in 1959, they are replaced by Kongo Dieto and Notre Congo. Some colonial newspapers intended for Europeans open their columns to African collaborators, such as the liberal newspaper Avenir, which beginning in 1956 invites Congolese such as Philippe Kanza and Joseph-Désiré Mobutu. Most newspapers created by and for the Congolese have a Catholic tendency: La voix du Congolais (1945-1959) and La Croix du Congo (1945), renamed Horizons in 1957. That same year the social Christian Présence congolaise is launched, as is the nationalist Congo, which considers itself the first independent weekly managed by Congolese. But the colonial authorities put an end to it before the year is out and put together a team of more moderate Congolese journalists who are given the means to launch the weekly Quinze. In 1958, the MNC-Lumumba's Independence appears for the first time. |